The American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) last week released its first Cancer Disparities Progress Report, raising awareness of the toll cancer exacts on racial and ethnic minorities and other underserved populations. The report, launched at a September 16 virtual congressional briefing, also highlights areas of progress in reducing cancer health disparities and recommendations for achieving health equity.

“This inaugural and historic progress report will provide the world with a comprehensive baseline understanding of our progress toward recognizing and eliminating cancer health disparities from the standpoint of biological factors, clinical management, population science, public policy and workforce diversity,” John Carpten, PhD, of the University of Southern California Keck School of Medicine, who chairs the AACR Minorities in Cancer Research Council and led the steering committee that created the report, said in a press release. “It highlights progress but it also initiates a vitally important call to action for all stakeholders to make advances toward the mitigation of cancer disparities for racial and ethnic minorities and other underserved populations.”

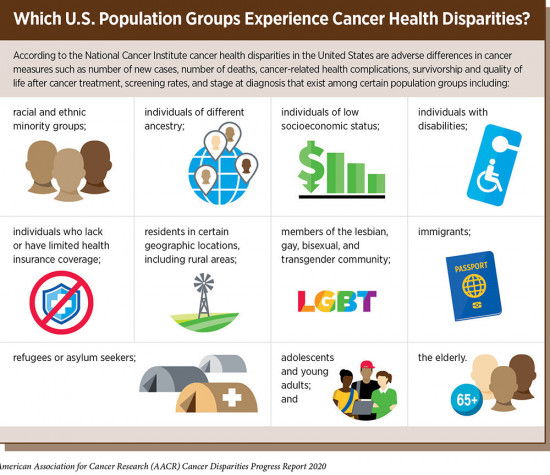

While research and the development of new treatments have led to much progress against cancer, they haven’t benefited everyone equally.

Source: AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2020Courtesy of AACR

Findings of the report include:

- African Americans have had the highest overall cancer death rate of any racial or ethnic group for more than 40 years.

- Blacks have higher incidence or death rates for many of the most common cancer types, including breast, colorectal, lung and prostate cancers.

- Latinos have lower overall cancer incidence and death rates than whites, but higher rates of liver, stomach and cervical cancer and childhood leukemia.

- American Indians and Alaska Natives also have lower overall cancer incidence and death rates than whites, but a higher rate of liver cancer and higher mortality from stomach and kidney cancers.

- Asians and Pacific Islanders have the lowest overall cancer incidence and death rates, but have higher rates of nasopharyngeal, stomach and liver cancers.

- Latinos have the lowest rate of colorectal cancer screening while American Indians and Alaska Natives are least likely to be screened for breast cancer.

- Bisexual women are 70% more likely to be diagnosed with cancer than heterosexual women.

- People with low incomes and those lacking health insurance have higher cancer incidence and death rates.

“Complex and interrelated factors contribute to cancer health disparities in the United States,” according to the report. “Adverse differences in many, if not all, of these factors are directly influenced by structural and systemic racism.”

Source: AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2020Courtesy of AACR

Some of these factors are social determinants of health, including inequities in socioeconomic status. On average, racial and ethnic minorities have lower incomes than whites, are less likely to have health insurance and are more likely to live in neighborhood with more pollution and less access to healthy food. They are also less likely to receive the highest quality cancer care and treatment.

Disparities in underlying risk factors also contribute to disparities in cancer rates. For example, Asian Americans are more likely to have hepatitis B, which can cause liver cancer, and gay men are more likely to have HIV, which is a risk factor for some types of cancer. There are also “striking racial and ethnic disparities” in potentially modifiable cancer risk factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, poor diet, physical inactivity and obesity.

Genetic factors also play a role. Racial and ethnic minorities have long been severely underrepresented in clinical trials, and understanding of how cancer develops these populations is lacking. Several initiatives to address gaps in knowledge about cancer biology in diverse populations are currently underway.

“It’s not OK that in the United States, African Americans have had the highest overall cancer death rate for more than four decades,” said report steering committee member Rick Kittles, PhD, of City of Hope in Duarte, California. “We are now able to genetically screen many tumors and use the information to make better clinical decisions for patients. Yet the majority of the data on cancer-associated mutations come from white people. So, many of these breakthrough new treatments may not be as effective for Black people and Latinos, who arguably need it more than other groups to continue to close the health disparity gap.”

While much work remains to be done, the report finds that there has been progress toward reducing disparities in recent years. For example, the differences in the overall cancer death rates for African Americans compared with whites has declined from 33% higher in 1990 to 14% higher in 2016. What’s more, diversity-focused training and career development programs have increased racial and ethnic diversity among cancer researchers and medical providers.

But the COVID-19 pandemic could imperil this progress. Some of the same groups that experience the greatest cancer health disparities are also experiencing disparities related to COVID-19. The report notes that the new pandemic is expected to worsen existing cancer disparities due to its disproportionate impact on racial and ethnic minorities and other underserved populations.

The report concludes with a call to action to policymakers and other stakeholders to eradicate social injustices that are barriers to health equity, such as providing robust and sustained funding increases for agencies and programs tasked with reducing cancer health disparities, ensuring that clinical trials include diverse participants and supporting programs to ensure that the health care workforce reflects the diverse communities it serves.

The progress report has been in the works for two years and was slated to be released in March, but that plan was disrupted by the COVID-19 crisis, AACR CEO Margaret Foti, PhD, MD, said at last week’s briefing.

The report is in keeping with AACR’s focus on racial, ethnic and other disparities. Racial inequity was a key theme of this year’s AACR Virtual Annual Meeting, and the organization will hold its annual Conference on The Science of Cancer Health Disparities in Racial/Ethnic Minorities and the Medically Underserved, chaired by Carpten, in early October.

“The AACR has long recognized the need to address cancer health disparities through its programs and initiatives,” Foti said. “Our organization has a dedicated history of proactively working in a number of ways to address the enormous public health challenge of cancer disparities.”

Click here to read or download the full AACR Cancer Disparities Progress Report 2020.

Comments

Comments