Losing your hair can be one of the most devastating side effects of cancer treatment. Experts estimate that as many as 10 percent of people refuse recommended chemotherapy because they’re worried about losing their hair. But a technology now becoming widely available in the United States can help prevent hair loss.

Stephanie Wells, a college professor who lives in Oakland, California, didn’t expect to need intensive treatment when she was diagnosed with Stage I breast cancer in August 2016. And she didn’t expect to lose her hair.

Wells, now 52, has a family history of breast cancer and got mammograms twice a year, so she caught hers early. But because of the characteristics of her tumor, her doctors wanted to play it safe. After surgery, she received Taxol (paclitaxel) once weekly for three months, underwent radiation every day for six weeks and took Herceptin (trastuzumab) for a year.

“It was surprising how long my treatment lasted, considering how early my cancer was diagnosed,” Wells says. “I decided I’d do whatever I had to do to prevent recurrence, but it was more than I bargained for—I guess cancer always is.”

At least half of the quarter million women diagnosed with breast cancer each year will receive chemotherapy that usually causes hair loss, or alopecia, according to Hope Rugo, MD, director of the Breast Oncology Clinical Trials Program at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center. Although it takes only a couple of weeks to start losing hair during chemotherapy, it can take months or even years to grow it back—and sometimes hair loss can be permanent.

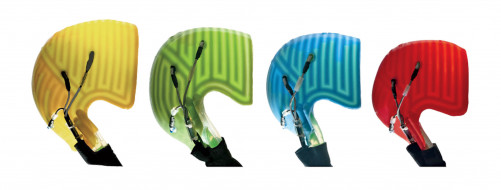

DigniCap silicone inner caps in different sizesCourtesy of Dignitana

Wells’s oncologist at UCSF told her about the benefits of scalp cooling technology and encouraged her to try it.

“Before, I thought maybe going bald would be empowering—I have a sense of self that baldness wouldn’t take away,” Wells says. “But I wanted to go out in public and not have people see me as a patient. At a time when I had lost control over a lot of things in my life, it was reassuring to look in the mirror and recognize myself.”

During each weekly Taxol infusion, Wells used the newly available DigniCap Scalp Cooling System from Dignitana, based in Lund, Sweden. She received a grant from HairToStay to help pay for it (see sidebar).

“The first couple of times it was uncomfortable—the cap is really tight,” Wells recalls. “It can be painful when your head starts to freeze for about five minutes, but then it’s completely numb. You have to get your head down to a cold temperature beforehand, then you have a couple hours of chemo, then they leave you frozen for another hour—it’s basically an all-day affair.”

Though Wells lost about 20 percent of her hair, her appearance remained pretty much the same.

“I knew, my hairdresser knew, but you couldn’t tell by looking at me,” she says. “It was not detectable to anyone who didn’t know.”

How It Works

Traditional chemotherapy kills rapidly dividing cells. In addition to cancer cells, the medications can also harm fast-growing normal cells, such as those in the gastrointestinal tract and hair follicles, leading to familiar side effects like nausea and hair loss.

Scalp cooling constricts blood vessels and reduces the amount of chemotherapy drugs that reach the hair follicles. It also slows down the metabolism of those cells so they’re less sensitive to chemo, according to Rugo.

Although scalp cooling has been used for decades in Europe, it’s a relatively new option in the United States.

“The idea has been around for a while. One of my patients was told to use a bag of ice in a shower cap maybe 50 years ago,” says Laura Esserman, MD, director of UCSF’s Carol Franc Buck Breast Care Center.

“If hair loss is something our patients really care about, it’s something we should really care about,” she continues. “It’s an aspect of cancer care that just robs people of a feeling of wellness, dignity and privacy. An essential part of our job is to be an advocate for the people we care for.”

"It was reassuring to look in the mirror and recognize myself.”

Several companies offer manual cooling caps that must be kept in a special freezer or on dry ice and changed every 20 to 30 minutes as they thaw out. Penguin Cold Caps makes its own cap, while Arctic Cold Caps, Chemo Cold Caps and Wishcaps use Elasto-Gel caps. This method reduces hair loss in many cases, but it can be hard to get a tight enough fit and keep the caps cold enough.

Manual cooling caps are not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and cancer centers don’t provide them. But more than 100 centers have installed freezers—many of them donated by The Rapunzel Project, a nonprofit started by two Minnesota breast cancer survivors—to store caps brought in by patients.

DigniCap and another scalp cooling system from Paxman, based in Huddersfield, England, use refrigeration to automate the process. These systems circulate a coolant through tubes in a tight-fitting silicone inner cap, which is covered by an insulating neoprene outer cap. Computer controls gradually lower the temperature and maintain it near freezing. Both systems are available at more than 100 cancer centers in the United States; The Rapunzel Project maintains a list of centers equipped with cold cap freezers and DigniCap or Paxman machines.

Richard Paxman’s grandfather invented a beer cooling system for breweries in the 1950s. His father, Glenn Paxman, now the company’s chairman, drew on the family’s expertise in refrigeration after his wife, Sue, was diagnosed with breast cancer. She used one of the early manual caps, but it didn’t work for her, prompting Glenn and his brother Neil to develop an automated cooling system in the late 1990s.

“When I was 10, my mum was diagnosed with breast cancer,” says Richard Paxman, now company CEO. “For all the family, seeing her starting to lose her hair was just the hardest thing and indeed the first visible sign she was ill. That was the first time she actually cried. Our personal understanding of how hair loss impacts someone going through chemotherapy is our driving passion.”

The DigniCap received FDA clearance in December 2015 for women with breast cancer, after it was shown to be safe and effective in clinical trials. In July 2017, it was cleared for women and men with any type of solid tumor. The Paxman system received FDA clearance for breast cancer in April 2017, and the company has requested clearance for all solid tumors.

Rugo, Esserman and their group at UCSF spearheaded the DigniCap trials. Richard Paxman was part of a team that conducted a similar study of the Paxman system, led by Julie Nangia, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. Both studies were published in the February 14, 2017, Journal of the American Medical Association.

“There were a lot of myths and tales, like you had to start the cooling four hours before chemotherapy and continue four hours after, but there was little science,” Esserman says. “We really needed trials by credible institutions to figure out if this works.”

The DigniCap trial enrolled 122 women with Stage I or II breast cancer at five centers. They all used chemotherapy drugs known as taxanes (85 percent used docetaxel; 12 percent used paclitaxel). Participants in the DigniCap group started wearing the cap half an hour before chemotherapy infusions and continued for one and a half to two hours afterward. A matched control group didn’t use scalp cooling.

Two thirds of the women who used DigniCap lost less than half their hair, including five who had no hair loss. More than 80 percent of those treated with paclitaxel for 12 weeks—the regimen Wells used—kept most of their hair. In comparison, everyone in the control group lost most of their hair.

Women using the Paxman Scalp Cooling SystemCourtesy of Paxman

The Paxman trial enrolled 182 women with early breast cancer at seven U.S. centers. Nearly two thirds received docetaxel or paclitaxel, while the rest used the more toxic doxorubicin. They were randomized to use scalp cooling starting 30 minutes before and continuing 90 minutes after chemotherapy or not to use scalp cooling.

Half the women who used the Paxman system lost less than 50 percent of their hair and did not need a wig or head covering, while everyone in the control group lost most of their hair. But results differed according to the type of chemotherapy: 65 percent of those using the taxane drugs kept most of their hair, compared with just 22 percent of those taking doxorubicin.

The most common side effects were headaches, scalp pain and chills, which were usually mild or moderate and often lessened after the first session or two. A few people in each study dropped out because they felt too cold.

Some providers have expressed concern that scalp cooling could allow cancer to spread to the scalp. But scalp metastasis is rare and usually occurs only in people with metastasis elsewhere in the body, according to Rugo. Long-term studies in Europe have shown that scalp cooling does not increase the risk of scalp metastasis and has no effect on survival.

Laura Esserman, MD.Courtesy of UCSF/Elena Graham

Glenn Paxman and Richard PaxmanCourtesy of Paxman

A Sense of Control

Scalp cooling does not always work. A good fit is key, and hair loss can occur if there are gaps between the cap and the scalp. Esserman says further research is needed to determine the effectiveness of scalp cooling with specific chemotherapy regimens and how much cooling time is needed.

“Four hours pre- and post-chemo seemed unreasonable,” she says. “We tested two hours after, based on drug pharmacokinetics plus a 30-minute cushion. Others showed that one and a half hours works. I’d like to see a time de-escalation study to see how short you can go. The time before and after makes it difficult for cancer centers to operationalize, which makes it hard to bring the price down.”

Cost is a major consideration. Manual cold caps are usually rented as a kit with a set of caps, supplies and a portable cooler for $300 to $600 a month. The DigniCap and Paxman scalp cooling machines are typically rented or purchased by cancer centers and patients pay a fee to use them. The cost typically ranges from $1,500 to $3,000 for a full course of treatment.

Considered cosmetic, scalp cooling is generally not covered by insurance. Many experts predict that reimbursement will become easier now that the automated systems have received FDA clearance and more people with more types of cancer are using them. Meanwhile, financial assistance is available (see sidebar).

Although women with early breast cancer make up the majority of people who have used scalp cooling to date, women with advanced metastatic breast cancer and men and women with other types of cancer have also seen good results.

“I did not want people to treat me as a victim. I wanted them to treat me as they always had, and the loss of my hair would have been a constant visual reminder of my illness,” says Allen Wasserman, 59, an attorney in Weston, Connecticut, who used the DigniCap while undergoing treatment for stomach cancer.

“When the cooling process starts, you get that headache you get when you eat an ice pop too fast. That feeling subsides after a minute or two and you adjust to the cold,” Wasserman continues. The results, he says, were “nothing short of a miracle. You lose a lot of control over things when dealing with cancer, but scalp cooling allows you to retain control over your appearance.”

Researchers are working to develop targeted therapies that don’t cause hair loss, but today a majority of patients continue to receive cell-killing chemotherapy. “The best thing is to develop new treatments that both cure cancer and avoid side effects,” Esserman says. “But in the meantime, we can reduce suffering by preventing hair loss.”

Hair loss is not life-threatening, and some people feel that losing your hair is a small price to pay for saving your life. But it can have a big psychological impact, and it can tell the world you’re living with cancer.

“It might seem frivolous—I thought so myself at first—but keeping my hair turned out to be important at a core level,” Wells says. “If I didn’t feel terrible, I could forget for a minute that I had cancer. I could choose who knew. It allowed me to remember there’s more to my life than cancer.”

Click here to read the sidebar “Leveling the Playing Field.”

Comments

Comments